Supporting companies in making R&D tax credit claims has its challenges. And in recent times, changes to the UK R&D tax credit claim process, and a more assertive stance from HMRC, have understandably made many claimant companies and accountants more cautious, particularly when it comes to software-related claims. I regularly speak to accountants who are comfortable with claims in areas like mechanical engineering or manufacturing, but who feel far less certain when the word “software” appears.

Why is that – and what can be done to improve confidence around software claims?

The R&D tax credit scheme supports companies and projects that seek to make scientific or technological advances – including in “software”. However, software claims tend to attract more hesitation for a few specific reasons.

- Software is abstract. You can touch a mechanical prototype. You can see a materials experiment. Software advances, by contrast, may sit deep inside a technology stack – in algorithms, data handling, performance constraints, or architectural decisions – that makes them harder to explain clearly and articulate the advance unless the right questions are asked.

- “Software” is an unhelpful label. In many claims, software is the end product – but it is also a tool used during development. The DSIT Guidelines are clear that: “A process, material, device, product, service or source of knowledge does not become an advance in science or technology simply because science or technology is used in its creation.” For software, this means that simply building new software – even very impressive software – does not automatically mean there has been a qualifying advance. A company may have come up with an innovative piece of software that, for example, revolutionises the marketing industry – however, “marketing” is not a field of science or technology – so if they were using standard software routines, this advance would not in itself be qualifying R&D. This nuance can be hard to get across to a competent professional who considers the innovative nature of their product as justification as qualifying R&D.

- Increased HMRC scrutiny. Historically, claims have been submitted for bespoke software projects that involved little or no genuine technological uncertainty. As a result, software claims have attracted more compliance checks, which in turn has led to more doubt around the eligibility of software claims. And then when HMRC do ask specific questions, they can be quite inconsistent and sometimes get quite conceptual – a further challenge of the abstract nature of software, and the lack of technical knowledge and consistency by HMRC reviewers.

- A rapidly changing baseline. Today more than ever, particularly where AI is involved, what was an advance last week is baseline technology today. This can make it hard to identify an advance against a rapidly moving baseline.

- Techies can be conservative. I’m stereotyping a little here, but software engineers often don’t shout about their work and are conservative about their achievements. This isn’t helped by the fact that day-to-day programming is about problem solving – so they may not naturally differentiate between routine problems and those that go beyond the baseline. All of this means that it can be challenging to coax details of advances when they are modest about them.

- Software projects are rarely linear. Back in the day, software development tended to follow a waterfall approach – you start with understanding requirements, go into solution design, develop the solution, test it, etc. Most software development teams now use agile methodologies – work is carried out by cross-functional teams (not purely technical), work is carried in short sprints, and the scope evolves with reviews and re-prioritisation between sprints. Key differences are that there isn’t a one-off stated specification at the start of the project, pure technical work crosses over with other non-R&D functions (such as requirements analysis and user experience design), and work is often more a long-term programme of continual activity than discrete projects. This can make project definition and R&D boundaries harder to identify than with more conventional project approaches.

So, how do we get past this and increase our confidence in software claims? The role of the accountant or advisor is not to assess the eligibility of R&D, but to help the competent professionals to do this. But I firmly believe that there is an important role in hand-holding the competent professionals through the process.

I believe that it starts with the way we talk to the competent professionals about what is and isn’t qualifying R&D for tax purposes. In my experience, just giving them a copy of the DSIT Guidelines and asking them to consider it for their software projects isn’t effective.

There are a few tools I regularly use to help software competent professionals to understand the scope of qualifying R&D, and to start to get project details for case studies:

- I find it useful to talk up-front about advances not in terms of “software” – but fields with names such as software engineering, software architecture and data science. This isn’t just semantics – a more refined terminology forces someone to think less about the output (the what) and more about what enabled its development (the how). For example, you might ask what was lacking in the field of software engineering that meant that they couldn’t use existing approaches, techniques and tools to achieve what they sought – and what advances did they seek to enable this.

- To focus on the overall advances, it can be helpful to make it very explicit that they need to focus on technology beyond just the company’s own systems and project use cases – it is all too easy to think about how the company has benefited from the work, and to loose site of the requirement that advance needs to be overall within the field.

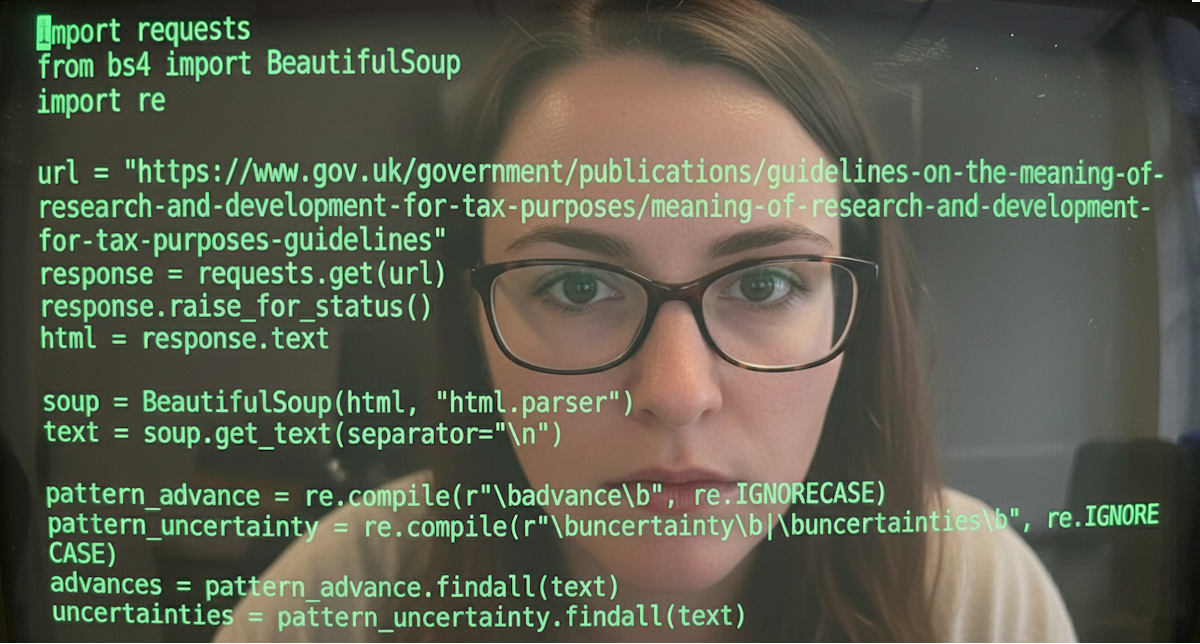

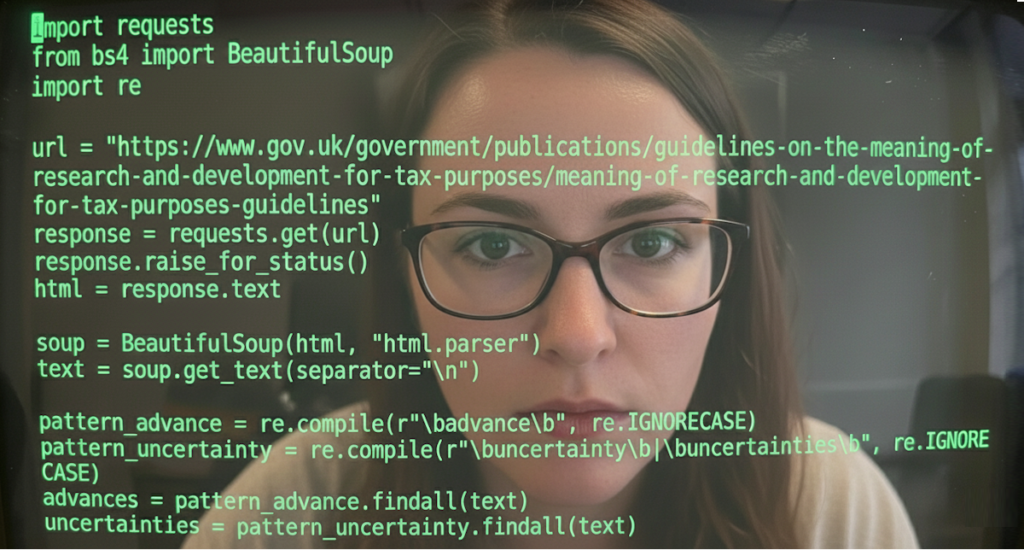

- To help them to think about the relevant technological uncertainties, it can be helpful to ask the software competent professionals to think about areas where they had to undertake technical experimentation, prototyping, or use trial and error – this might suggest some qualifying technical advances and uncertainties that warrant more detailed discussion.

- To help them understand what does and doesn’t qualify and the boundaries of R&D, what is and isn’t a qualifying advance and what is and isn’t a valid uncertainty, I often use hypothetical examples for the types of things that would or wouldn’t qualify in a project such as theirs. Examples can be powerful, but by keeping to hypothetical examples, you won’t be leading them too much.

- A key area that often doesn’t come through well in a case study is the baseline of science or technology. Articulating this strongly can avoid unnecessary questions if the case study gets across what the state of the art was in the field at the outset of the project, particularly if the baseline has since moved on. And just like the advance, the baseline needs to be in the field of science or technology, and not in an industry that the project is supporting (as mentioned earlier, end-user industries such as marketing are not fields of technology, and so the baseline should not be about what was lacking in that industry).

- Often, the first claim a competent professional is involved in can be challenging. Beyond understanding the Guidelines and where their work qualifies, there is the challenge that claims are retrospective, and you can sometimes be looking nearly three years back in time. Ask someone what they were doing last week, let alone years ago, most people need to think hard or look back through notes and documentation. As mentioned, agile projects add further complications to this, notably that there may not be formal point-in-time documents such as specifications – and where they exist, they likely will record what was developed, but not why. I am a fan of Architectural Decision Records – living documents where a competent professional (or team) can record technical decisions made throughout the project along with the reason why. Recording this context along the way is like gold dust when it comes to a future claim. Technical retrospective meetings can be useful as well, where this kind of detail can be recorded on a regular basis (e.g. quarterly). This means information is to-hand when the case study for a claim is written later on.

- A tool I sometimes use to help get the competent professional in the right mindset is to ask them to think about what work would they have been proud of from a technical perspective – such that another software engineer outside their business or commercial sector could appreciate as an advance and could benefit from. I find that this sometimes helps them to focus on overall advances (not just advances related purely to their project and company’s industry) and to focus on technological advances rather than commercial ones. This is merely a leading question to support the conversation but can help put the conversation on the right track.

Ultimately, strong software R&D claims are built on good technical conversations. When accountants, advisers and engineers speak the same language, competent professionals really understand what does (and doesn’t) qualify, and the R&D work projects can be articulated confidently, software R&D stops feeling like a grey area.

At Articulate, we support all of this day-in, day-out. If you are an accountant or R&D advisor and think that our software specialist (or specialists in other fields) could add some value to your conversations with your clients, do let me know. Our consultants have worked in scientific and technology fields (including software development!) and each have years of experience supporting claimants with their R&D claims.

About the author: I lead Articulate R&D a small team of sector-specialists who worked in various fields of science and technology and technical writers. We work with accountants, R&D specialist firms and their clients to help claimants understand project requirements, qualify R&D projects and write robust case studies for R&D tax credit claims. Contact me if you’d like to chat.